So Who Takes Care of the Calf?

The short, simple answer to this question is, of course, the cow. That's her job. The role of the cow specifically, and cow/calf production systems in general, is to profitably turn forage into beef through the production of calves. Our entire management effort centers on providing the inputs required for the cow to do her job. Not providing these inputs diminishes her chances of successfully playing her role in the cow/calf production system. As cattle producers, our responsibility is to ensure that the fundamental inputs of water and forage are provided along with supplemental nutrition and sound animal husbandry and management that prevents disease and promotes herd health.

Like every living thing, the cow needs water which is the most important nutrient. Water is essential to maintaining all bodily functions and, if limited, results in lower productivity and performance. Clean water should be provided without restriction. Production systems that rely on surface water are at the mercy of adequate runoff from rainfall to provide the cow's drinking water. During winter in our northern climates, surface water is more likely to be frozen and unavailable, so alternatives must be used.

The quality of surface water can vary greatly, especially during times when the quantity is limited. As surface water evaporates and is not replenished, as in a drought or extended dry period, elements in the water become more concentrated and could reach dangerously high levels. It is important to understand surface water quality through occasional testing. Well water should also be tested at least once every few years for elements that can cause health or nutritional issues. Sulfur, iron, nitrates, sodium and heavy metals are examples of elements found in water that, if excessive, may contribute to health or nutritional problems.

The nutritional status of the cow throughout the year is critical for success. Grazed forage provides the majority of the cow's nutrients and is the most economical source of energy. Therefore, an entire management plan should focus on providing a sufficient quantity of grazed forage of a quality closest to the cow's requirements.

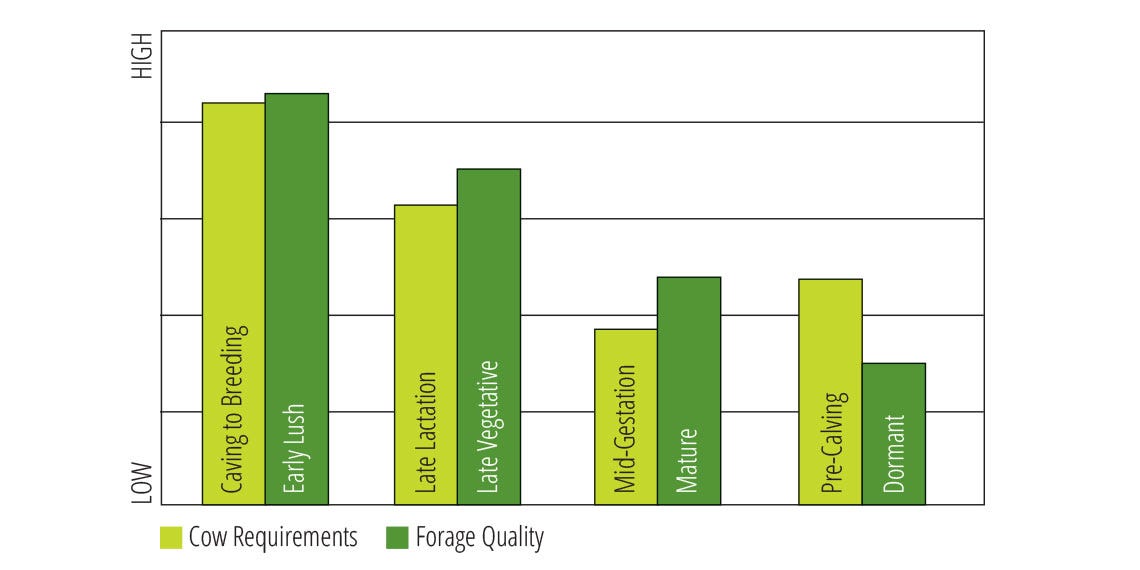

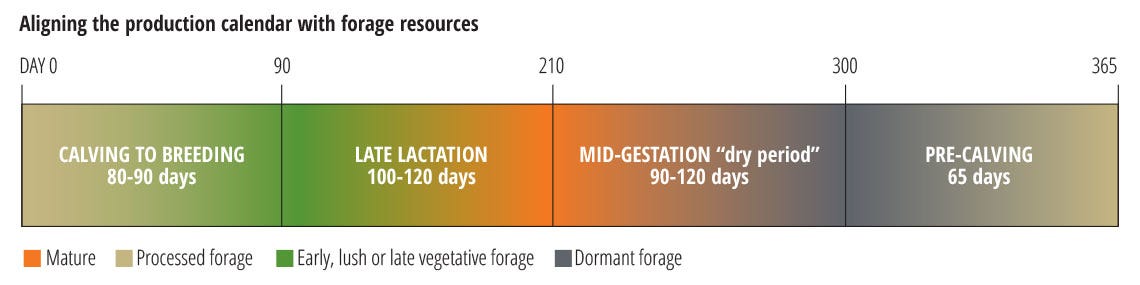

The cow's requirements vary throughout the year as she moves through the four phases of production: calving to breeding, late lactation, mid-gestation, and pre-calving. Likewise, the quality of the forage and level of nutrients available to the cow varies throughout the year and are categorized into four growth stages: early vegetative, late vegetative, mature, and dormant. From a nutritional perspective, we manage cattle to ensure that when the cow's requirements are at the highest, calving to breeding, she has the highest quality forage, the early vegetative stage, available to her. Therefore, the timing of calving is critical in providing the needed nutrients at the lowest cost to meet the cow's requirements and, ultimately, care for the calf.

One way to measure the nutrition status of the cow is through body condition scoring (BCS). Higher body condition (BCS 5 and 6) at calving provides energy for milk production and results in higher reproductive performance than cows with lower scores (BCS 4 or less).

Milk constitutes nearly all of the calf's nutrient supply for the first four months of its life. Cows that are genetically capable of supplying high quantities of milk mobilize body fat to ensure that the milk production is adequate, even when high quality forage is available to them. Managing body condition is how we assess the amount of body fat available for mobilization during early lactation, and how we begin taking care of the calf even before it's born.

During mid-gestation, the cow's nutritional requirements are at their lowest of the production cycle. This is the most opportune time to replace body condition lost during lactation before the cow's requirements increase substantially in the pre-calving phase. The pre-calving phase the sixty days prior to calving is when approximately 70 percent of fetal development occurs. By ensuring that the cows are in good body condition and that the diet meets their increasing nutritional requirements, we're indirectly taking care of the prenatal calf. The calf's neonatal vigor, the ability to quickly rise and nurse, and health status are impacted by the nutritional status of the cow during the pre-calving phase.

Recommended herd health and vaccination programs are regionally specific. Vaccination protocols are best outlined by local veterinarians. The nutritional status of the cow pre-calving, along with a complete cow vaccination program, determines the quality of colostrum or first milk provided to the calf. Colostrum provides the sole source of antibodies, providing passive immunity from pathogens until the calf's active immune system begins functioning. The health of the neonate calf is entirely dependent on how well we take care of the cow pre- and post-calving.

The first time we routinely, directly intervene in the care or the calf is when we vaccinate to prevent common infectious disease. These vaccinations are administered after the calf develops a functioning immune system, about three months of age, but before weaning. By three months of age, the passive immunity provided by the colostrum is no longer providing immunity.

Putting it all together

The way we manage nutritional inputs begins with the establishment of the production calendar. The calendar for the herd begins with the birth of the first calf, which in most cases should be about thirty, but not more than sixty days before forage is in the early vegetative stage of growth. The cow's nutrient requirements are highest in the third month after calving, coinciding with her peak milk production. Maximum forage quality and quantity begins about a month after first green up. Cows calving thirty days before green up are peaking in their milk production at the time when the forage is most capable of meeting the higher protein and energy requirements, and the calf is of sufficient size to handle the volume of milk.

Mineral elements both macro and micro minerals are the most common, critical nutrients lacking in grazed and supplemental forage. Consequently, a high quality, weatherized, loose mineral designed for the region should be offered free-choice throughout the year. This is essential in filling the mineral shortcomings in the forage.

After weaning, the cow's nutrient requirements drop to the lowest levels during the production cycle. Even though the mature forage is of relatively lower quality than earlier in the season, this is the best opportunity for the cow to regain body condition. Late season, mature forage is often capable of meeting the cow's protein and energy requirements, while dormant forage is more often marginal. If the grazed forage contains a minimum of seven percent crude protein and 45-48 percent total digestible nutrients (TDN), the only supplementation required is mineral until about 60 days prior to calving. The testing of late season pasture forage is highly recommended to determine if the quality is sufficient to meet the cow's protein and energy requirements.

The cow's nutrient requirements increase substantially during the pre-calving period, driven by the developing fetus and associated tissues. It is important to make sure we are meeting the cow's requirements during this period to ensure proper fetal growth, maintain the cow's body condition and promote the production of high quality colostrum. Dormant standing or lower quality forages won't meet the requirements during this period. Replacement forage or supplemental feed is often required through the pre-calving phase, and until there is sufficient new crop forage. A high quality, free-choice mineral is essential. As the cows calve, the entire process begins anew.

A quality water source, adequate nutrition based on the cow's changing requirements and a solid understanding of managing BCS these form the foundation of a cost effective cow/calf operation. Our job is to build that foundation and effectively align the production calendar to the forage resources available to meet the needs of the cows.

So, who takes care of the calf?

If we do a good job of taking care of the cow, meeting her needs pre- and post-calving, the cow will take care of the calf.